It may sound odd that by killing a few we can save many, but it IS working!

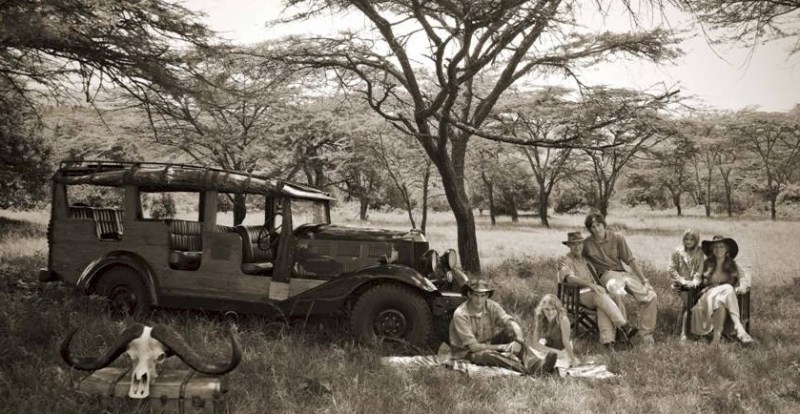

Trophy hunting. Just uttering those two words during a conversation is bound to liven things up a bit. Many people have very passionate opinions concerning trophy hunting, both positive and negative. The concept even engenders debate and division within the hunting community.

But if we can set aside the emotion that the subject of trophy hunting typically elicits, we will see that trophy hunting is in fact a sound and effective conservation and wildlife management tool. The evidence is becoming increasingly convincing that, as counterintuitive as it may seem, allowing a few animals to be hunted does indeed benefit the larger population and the protection and long-term viability of a species.

In a nutshell, here's how it works (we'll break down each of these components in a moment):

- The wildlife management and conservation programs that are vital to protect and otherwise benefit exotic big game animals (and by extension, the other animals in the ecosystems inhabited by big game) require money to operate.

- Funding for those wildlife management operations is, for many countries, an ongoing and, at times, losing struggle.

- Wildlife management program scientists and biologists have determined that a small number of specific animals in a population can and/or should be removed each year for the benefit of the health of the larger population.

- Trophy hunters are willing and able to step in and contribute to solving both issues by providing operating funds and removing problem or surplus animals.

Let's quickly look at each of the components in this simplistic, though accurate, breakdown.

1. Wildlife management programs require a lot of money to remain active and effective.

Money is needed for equipment, technology, infrastructure, utilities and other support systems, personnel support and people's salaries - the stuff that any agency or business needs to stay in business. (And bear in mind that wildlife management and anti-poaching programs are not in the business of selling widgets or a market item.)

Their business is to spend money to increase their effectiveness in protecting and enhancing habitat and wildlife.

2. It's difficult to say how much money is consumed by all of the various animal protection and conservation programs around the world, but it's safe to say that it's an astronomical figure.

For example, last year in South Africa alone the government earmarked $7 million in extra funding to increase anti-poaching security measures in its national parks. It also engaged municipal police and military forces to assist in protecting threatened wildlife. And those measures are still not sufficient to prevent the rise in poaching, let alone doing things to increase and improve habitat. Last year, 22,000 elephants were killed by poachers in South Africa.

The Save the Rhino conservation and rhino protection organization gives hundreds of thousands of dollars every year to various rhino protection agencies. And it's still not enough to stem the tide of poaching losses.

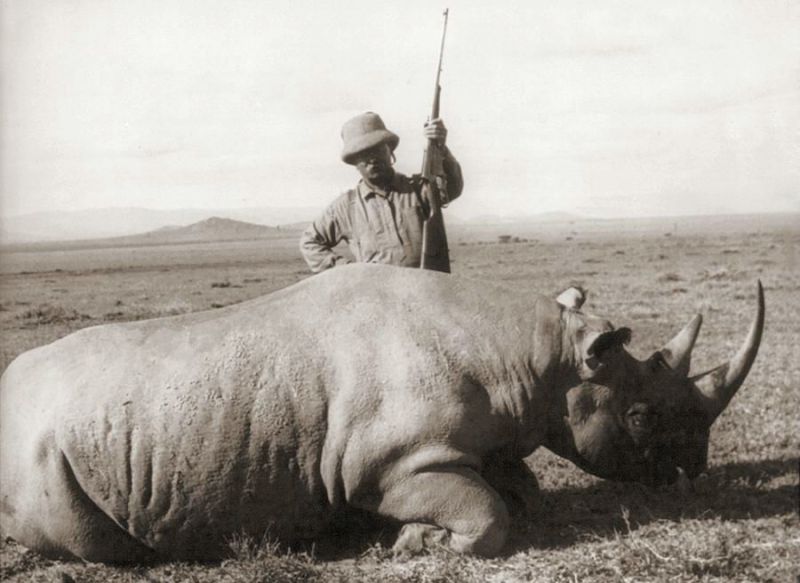

3. Wildlife scientists and biologists closely monitor big game animals under their charge, both as individual animals and the population as a whole.

It is often the case concerning big game animals like rhinos or bull elephants, that older males that are nearing the end of their viable reproductive lives may become violent and dangerous to other members of the herd or population. Older males have been known to injure and even kill younger males, females and calves.

Their removal is beneficial for the safety of the larger population. A few are relocated to zoos and the like, but there aren't enough zoos or shelters able or willing to receive and care for animals that are already determined to be dangerous. Wildlife management agencies themselves have the power to remove by extermination such animals, and they do when no other options are available.

Namibian biologists, for example, have determined that up to five rhinos per year may be removed without harming the health and growth of their rhino population. That doesn't mean that they do actually remove five animals each year, simply that that has been scientifically determined to be an acceptable number, of which certain animals of that number are necessary to remove for the reasons stated above.

4. Hunting - "trophy hunting" - is being seen by an increasing number of scientists, conservationists and wildlife experts as a viable tool, with multiple positive influences, in supporting the larger agenda of protecting wildlife and endangered species.

Trophy hunting clearly provides a significant source of revenue to conservation programs in countries that desperately need the funds.

A year or two ago an American hunter placed a winning bid of $350,000 in an auction for a Namibian rhino permit. ALL of that money was to go to support continuing rhino conservation. Protests and outrage from animal rights activists effectively stymied the hunt and the financial support the Namibian Black Rhinoceros Conservation Strategy would have received, until a recent decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to allow the import of rhino trophies from Namibia was released a few days ago. Now that $350,000 will go directly to fund more anti-poaching and rhino conservation.

There is an additional unfortunate part of that particular story, which is by no means the first or only example where misguided animal rights groups have done more to harm conservation efforts than to help them. It was reported that one bidder in that auction had placed a bid of one million dollars but withdrew the bid after receiving death threats from overzealous animals rights advocates.

Money in amounts like that has compelled some critics to hurl even more condemnation at trophy hunting and hunters who are willing to shell out hundreds of thousands of dollars for the opportunity to experience a big game safari and help conservation at the same time. That seems rather like asking a lifeguard to help save someone who's drowning and then condemning him for how he successfully went about it.

But accusations of bloodlust, overblown egos and questions of masculinity are misplaced. Trophy hunters, as much if not more than any other hunting demographic, are concerned and active conservationists, and their motivations for opening their pocketbooks have less to do with killing a big game animal than with what all hunters are concerned with: a vibrant and sustainable wildlife population that will allow them and future generations to continue to enjoy the hunting experience.

Author Richard Conniff, writing for TakePart, reveals that trophy hunters may be just about as concerned with supporting the communities and people who live in proximity to endangered species as they are with experiencing the hunt itself. Conniff says that a "new study suggests that big game hunters are not only aware of the close connection between protecting wildlife habitat and supporting local communities but are also willing to pay thousands of dollars extra to strengthen that connection."

The study he refers to was conducted by the James Hutton Institute in Scotland, where senior research scientist Anke Fischer and her coauthors surveyed 224 big game hunters, most of them with experience hunting in Africa.

Conniff continues, "The goal was to understand what they value in a hunting area and what might encourage them to come to Ethiopia. The survey calculated these attitudes in terms of what it called WTP: 'willingness to pay.' The hunters said, on average, that they would pay up to $3,900 more if they could be assured that 10 percent of their total hunting fees would go to local communities—and $2,000 less if that share ended up with the central government. Hunting in areas where domestic livestock was also grazing reduced the value of the trip by $2,000 on average. The potential to see lots of wildlife, including non-target species, caused a spike in WTP."

Environmental scientist Dr. Duan Biggs of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions (CEED) and The University of Queensland, also supports trophy hunting as a means to directly fund anti-poaching and conservation efforts, but also as the backbone of community and individual efforts that have proven to be highly effective in thwarting poaching at the local level. Dr. Biggs explains that locally run community conservancies are responsible for actively protecting wildlife from poachers and in leaving wooded areas intact for wildlife.

Many community conservancies, including 90% of those in Zimbabwe and 50% in Namibia, are sustained by trophy hunting. In 2013, trophy hunting and tourism supported 6,400 jobs and generated $7.7 million as well producing 500 tons of meat - two million high protein meals - for Namibia.

It should also be noted that trophy hunters account for a very large chunk of those tourism dollars as, according to Alexander Songorwa, director of wildlife for the Tanzanian Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, they "spend 10 to 25 times more than regular tourists."

How that translates to endangered species conservation is this: Trophy hunting supported community conservancies have helped to boost Namibia's elephant population from 7,500 to 20,000 between 1995 and 2013, while the range of lions has expanded to outside of state protected areas in the same period.

Even Save the Rhinos supports regulated trophy hunting as an effective conservation and management tool. They indicate that since 1968, South Africa has permitted the limited hunting of southern white rhino and data from the IUCN African Rhino Specialist Group shows that since hunting began, the numbers of southern white rhino have increased from 1,800 to over 20,000.

It only makes sense that well-managed trophy hunting is beneficial to the conservation and sustainability of game populations. We here in the U.S. have seen the very same model successfully used for decades to increase, stabilize and reintroduce animal populations across our country.

As one friend put it to me the other day, "There's not much difference [from trophy hunting] in allowing turkey hunting to raise money to help reestablish the turkey population in Wisconsin."

Hunters, whether they can afford an African rhino hunt or not, would do well to support managed trophy hunting. As of right now, it is one reliable tool for saving endangered big game that is clearly working.

Like what you see here? You can read more great articles by David Smith at his facebook page, Stumpjack Outdoors.

NEXT: The Great Debate: Trophy Hunting Versus Meat Hunting

https://rumble.com/embed/u7gve.v3to3h/