Celebrated conservationist Shane Mahoney continues our discussion of food systems, hunting as conservation, and creating a new paradigm for reaching the public.

We continue our conversation from last time with Shane Mahoney. Previously, Shane had talked about about food systems, the Wild Harvest Initiative and reaching the public with a bold new pro-hunting message. Here he discusses the act of sharing the harvest, conservation organizations supported by hunters and anglers, and state and federal programs funded by hunters/anglers and the public alike.

Given this mutual financial support of such programs, we should be able to find common ground in our efforts to save and maintain wildlife populations.

DAVID SMITH: It strikes me that it is hunters and anglers who foot a good portion of the bill for sustaining and maintaining wildlife. And yet it's almost a given that an angler or a hunter will share a portion of his harvest, often with people who don't hunt.

SHANE MAHONEY: In a general sense I think it is certainly natural to us. I think it is evolutionary in the sense that hunting cultures around the world, and we've always known this, the hunt [the point] for hunter gatherer societies was not the kill of course. It was the preparation for the hunt.

It was the praying to the animals before they went out to harvest them. There was obviously the excitement of this activity. There was the tracking of the animal, there was the killing of the animal. There was the butchering of the animal. There was the great feasting of the animals. There was the sharing of the meat all throughout the community. All of these things.

DAVID SMITH: The ceremony of it.

MAHONEY: Yeah. It was a seamless part of a whole. And the habit of sharing of course was critical because - and these were small human communities - it was not possible to live alone. Everyone needed to do things to make life work.

Rural communities know this very well to this day, of course. Growing up in rural Newfoundland not everyone had a horse. So the people who had a horse, you know, the neighbors borrowed their horse to plow their ground. To do whatever was necessary. And in return for that they did something for that neighbor. This was how it worked.

DAVID SMITH: And it still works that way.

MAHONEY: Sure it does! So hunting, for 99.99% of our existence, that's how we lived. And remember that all of what we see around us today is just the blink of an eye in terms of human history and time. And so we naturally shared.

It wasn't just that we were being generous.

MAHONEY: First of all, we have to put it in context. The successful hunters - and remember, not everybody was a great hunter in hunter gatherer societies. Some were better, some were not as good. Some were better arrow makers than others. There are always these talents in a community.

For those people, they had great stature of course, to be successful hunters. And part of that stature came from the fact that they were able to share this food. They felt good about it, but they also became regarded and respected. So there was this feedback, emotional feedback.

Nothing wrong with that. There was a little bit of vital ego involved, to say that I'm a good hunter and that I'm gladly willing to share. Of course the sharing of that meat allowed the community to thrive, children to be born, children to grow up healthy, and contribute to the community.

So the idea of sharing was deeply ingrained. And so too it was when women, who did most of the gathering, sought for tubers, nuts, berries, wild foods and so on. That too was all shared with the community. And of course we see that today, David. Someone harvests wild berries and they produce jams, and they give the jams to their friends and neighbors and so on.

In that sense, yes, we have a tradition, and a lot of attributes within us that are genetically beholden, that together helped to bring this system about and helped to ensure that we continue it.

And it is really true that the instant, in many cases, that the animal goes down, and you are eviscerating the animal, cleaning it, looking inside of it, seeing how fat it is, seeing how clean the meat looks, seeing how clean it smells...you know all of these that as hunters we do.

Almost at the same time, a lot of hunters - myself, I'm sure you, many, many hunters - reflecting through their minds already is the idea that 'we'll get that cut up now, you know, we gotta give some to mom and dad, get some made into sausage that I can share.' It's just deeply ingrained. This is a beautiful thing.

MAHONEY: This is part of the new narrative that has to be explained to the modern public, who have no idea about the scale of this. Which is why the Wild Harvest Initiative exists. We will explain this game of this.

But the other thing is that the same people who are sharing this food, as you say, help support an enormous community. Including the basic conservation programs of the United States and Canada.

Now, let me just say at this point, emphatically, hunters and anglers are not the only conservationists in our two countries. Hunters and anglers are not the only ones who pay for conservation in our two countries.

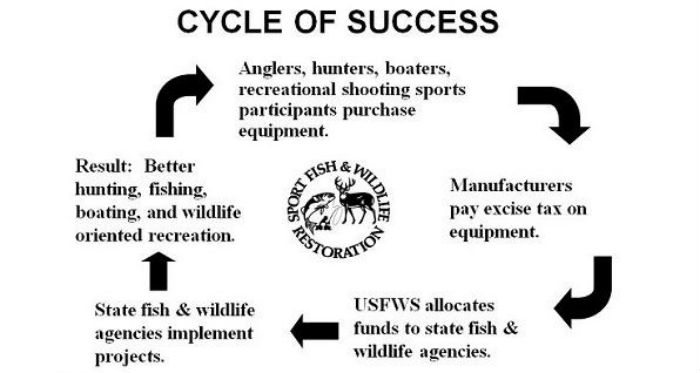

But over the last century, if you look at the way the funding models have worked, in the United States in particular, with Pittman-Robertson funding, the Dingell-Johnson Act, all of the taxes that are paid on sporting goods and firearms, and so on and so forth.

Hunters have provided a disproportionate amount of money certainly for the maintenance of all state agency conservation programs. That is an absolute desperate fact. It cannot be chased down and pinned to the ground and found to be untrue. This is an absolute fact.

Even today, 70% on average of the budgets of state agencies in your country are paid primarily out of hunters' dollars and taxes that I've just referenced. Now, there are lots of programs in the United States and in Canada - that are paid for, that have conservation benefits - that are paid for by the general public through taxation. The parks, for example, the national systems, US Fish and Wildlife Services, national and federal agencies and bodies.

But, the point there is, yes, everyone in society contributes in some way through general taxation. But the hunter and angler are also part of that, aren't they? They're also part of the general taxes.

So, no matter how you slice it, there have been - and I hate to use the word disproportionate, because it sounds like as hunters and anglers we shouldn't be...like beating our chests or something, which is really not what we've been about - but what we have then is disproportionate giving of this community, and the activism of this community.

MAHONEY: The number of NGOs, the Wild Sheep and the Ducks Unlimited and the Dallas Safari Clubs and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, etc.. (I hate not mentioning any, because I have to remember 10,000 of them, in order to come up with all of the ones that are out there.) There is just an amazing array of NGOs, many of which have a significant part of their membership coming from the hunting and angling community.

And so they [hunters/anglers] not only give back in the taxation of their activities, they not only give back by the payments for the right or the privilege to hunt and fish, by buying a permit or a license, they not only give back in the general taxation for conservation...they now give back again through the creation of these many NGOs, which raise enormous amounts of money for wildlife conservation in both our countries.

So these truths...this marvelous, beautiful idea that a group of people would become especially engaged in the conservation of wildlife extends all the way back to Theodore Roosevelt. More than a hundred years ago.

The Boone and Crockett Club in 1887, and many other groups agitating at the time.

And from the very beginning the hunter and angler was placed at the center of this movement. Never alone. There were lots of great conservationists and preservationists. John Muir...and all the other things that have been done in protecting great spaces and monuments and so on. We can't deny the tremendous conservation benefits of those things, and the tremendous cultural benefits, the great legacy that is there.

But the hunting and angling public for over a century have been, you know, just giants turning the millstone of conservation.

And of course the benefits are for everyone. It's not just the hunter who benefits from abundant wildlife. So too does the wildlife viewer, the wildlife photographer, the hiker, the mountain biker. You know, we all love and want wildlife in our lives.

Like what you see here? You can read more great articles by David Smith at his facebook page, Stumpjack Outdoors.

NEXT: Shane Mahoney Exclusive Interview, Part I: The Wild Harvest Initiative