Follow this trad bow checklist to quickly tune your traditional recurve or longbow for a more successful, straight shooting bowhunting season.

Bowhunting season is upon us. It's time - actually, it's well past time - to make sure your traditional archery gear is finely tuned and shooting true. This trad bow checklist should cover all the bases.

Whether you shoot a recurve bow, longbow or even a self bow there are things you should do before, during, and after the bowhunting season to make sure that your equipment is in top form. Traditional bows don't have all of the moving parts and gadgets that compound bows carry, but there are still a few things you can do to keep them shooting straight and true.

Make sure your bow fits you

Being able to pull a heavy draw weight isn't necessary to being a good bowhunter. If you can draw 70 or 80 pounds, that's great! But drawing a lower poundage bow may be a better option.

Pulling a 55-pound bow, even when you're capable of drawing more, will enable you to hold steadier and longer. It will also help you to concentrate more on your form, aiming, and shooting. Putting all those elements together is tough while muscling a heavy bow. Take things down a notch, and I'll bet you'll see a difference.

Also, choose a bow length that fits your stature and draw length. For example, those archers who have draw lengths of 28 inches will want a longbow length of no more than 68 inches. If you've got a draw length of 30 inches or more, a longbow between 70 and 72 inches should fit nicely. There are plenty of charts online that compare draw lengths to bow lengths to help you find the best fit.

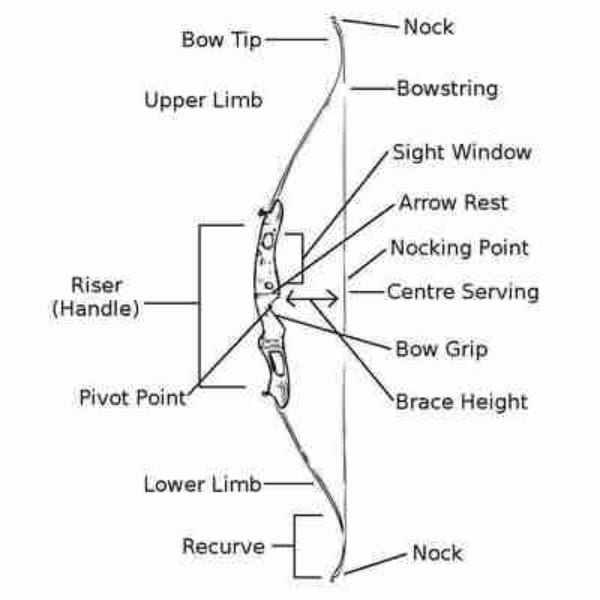

Check your brace height

Brace height is the distance between the bowstring and the deepest part of the bow grip. Adjusting your brace height will impact the arrow speed and the quietness of the bow. A shorter brace height will usually equate to faster arrow speed.

But personally, I think the quietness of the bow is the more important of the two. You may find that your bow shoots quieter with a longer brace height. I'm will to sacrifice a bit of arrow speed for a quieter bow.

The easiest way to adjust your brace height is to shoot with a Flemish string and adjust the string by twisting it until you get the quietest bow upon shooting. Adding twists to the string will increase brace height; removing twists will decrease it. With a new string, string your bow and leave it strung overnight to eliminate any new-string stretch. Then, measure the brace height, remove the string using a bow stringer, give it three twists, restring the bow, and shoot.

Each time you do this pay close attention to the sound of the bow as you shoot. Repeat the process, adding twists or removing them. It helps to have a friend listening with you so that the two of you can concur on what point the bow shot the quietest. When the bow is shooting at its quietest you have found the "sweet spot."

Recheck and adjust your brace height regularly, as over time your string will stretch or creep.

Adjust your nocking point

The nocking point is just a small metal crimp attached to the string that allows you to nock an arrow in exactly the same spot, each and every time.

To set your nocking point, use an bow square to set the location and pinch the nocking point on. That's all there is to it, although you may find that sliding the nock upwards up to a half-inch will improve your shooting. Experiment until you get it where you want it.

Checking the rest and centershot

If your arrow isn't lined up squarely with the string, your shooting accuracy may suffer. Check this by nocking an arrow, then by looking from behind the arrow using your dominant eye. Line up the string with the center of the bow's upper and lower limbs.

Ideally you want the arrow to line up perfectly with the string. That's called centershot. If the arrow looks out of alignment with the string, you may have some issues that should be addressed.

Most modern new bows come centershot. You can adjust the arrow rest and/or plunger to achieve centershot on these bows. However, not all bows have this capability. Some bows (like self-bows or fixed bows) may not have plunger or rest allowances. But you do have other options to compensate for the lack of centershot.

If your bow does not allow you to adjust centershot you can adjust your arrow spine. Shooting a lower weight arrow can compensate for a bow with a less than ideal centershot. You can also adjust your tip weight and arrow length. It will take a fair amount of trial and error experimentation to get it right.

One of the best explanations of centershot and adjusting for it can be found in the following video by Clay Hayes. Hayes explains the issue and the process of correcting it in detail.

The question of tiller

Tiller is the difference between the limbs of a bow. Most bows have a lower heavier limb that is stronger than the upper limb. This is because with the bow grip placement, the arrow is not nocked in the exact center of the string; it's nocked a little above center.

In order to compensate for this disparity, there is some difference in the strength of the limbs so that the arrow flies true as it leaves the string.

The process of creating a balance in the bow where the limbs work in harmony with one another is called tillering. There's a lot more to it than I can explain in this relatively short article. You can adjust to tillering issues in a number of ways, including changing your release or your nocking point. I have to admit, I have never done much with tiller...never had a problem with it.

Here's another excellent video that explains the nuances of bow tiller for various traditional bows.

Odd and ends

I think most traditional shooters are into instinctive shooting. But if you do use bow sights, make sure that they're properly ranged and firmly secured. Most archers also use bow quivers, but there are a few of us staunch traditionalists out there who still have a romance with back quivers. Whatever you use, make sure that everything is in good repair and that no arrows will be rattling and spooking game.

Speaking of arrows, your arrow setup is important. Generally, you want your arrows to be tip-heavy for better flight and penetration. You should also practice with field tips that are the same weight as the broadheads you'll be using during hunting season.

Again, I'm a romantic and I like wooden arrows. But I also shoot carbon arrows, depending on the bow I'm hunting with. I like spine-heavy carbons. I believe I get more momentum from heavy carbon arrows, which translates to better penetration.

The broadheads I choose are heavier than their lightweight compound bow counterparts. I go with 175-200-grain heads with inserts (or knapped stone arrowheads - I like those too!).

Make sure that you're comfortable with either your release aid, shooting glove, or finger tabs. Always carry a spare in the field with you. A lost or damaged release aid, glove, or tab can ruin your day if you don't have a back-up.

An arm guard is, in my opinion, a must. Most of the bowhunting I do is cool weather hunting and I wear long sleeves. But an arm guard keeps my sleeve tight and prevents it from billowing. It also puts me in a primitive frame of mind, which is a big reason I hunt with traditional or primitive archery equipment in the first place.

Quieting your bow

Moleskin is a bowhunters best friend when it comes to silencing a bow. We all know how critters can jump the string or spook at the sound of an arrow knocking against a riser. Put moleskin on the bow shelf to dampen that knock. Put a couple strips on the bow tips under the strings to quiet string slap, too.

String silencers of fur or rubber should be placed on your bow if you're a recurve archer. My personal preference is rubber for my commercial bow and beaver fur silencers on my primitive bow. Longbows tend to be naturally quieter than recurves so you may find them to be unnecessary if you shoot a longbow.

The most important part of tuning up

I've said this before and I'll say it again: practice. Whether you're a beginning archer or a long-in-the-tooth, experienced bowhunter, practice is everything. Practice not only increases your skill, but will help you discern which aspect of your equipment may need more attention than others. When you practice, you tune-up your mind as well.

You can shoot rabbits with a primitive self bow and arrows that you crafted yourself, or you can hunt elk with a top-of-the-line modern, laminated recurve bow that cost hundreds of dollars. Whatever you shoot, you need to shoot often if you are to become proficient and confident.

Tuning up your gear should be a part of every archers yearly routine, because it's fun and will make you a better archer. It can be as simple or as complicated as you want to make it.

Like what you see here? Experience more articles and photographs about the great outdoors at the Facebook page, Stumpjack Outdoors.

NEXT: HOW TO SELECT THE RIGHT ARCHERY BROADHEAD FOR BOWHUNTING

WATCH