Countless hunting stories have earned fame throughout cinematic history. They vary by genre, theme, and accuracy, but perhaps none is crazier than the tale depicted in the movie "The Ghost and the Darkness." The film chronicles the lions of Tsavo, two man-eating big cats that terrorized a construction project dedicated to building a railway bridge over a river in Kenya back in 1898.

The two maneless male lions are rumored to have killed and eaten 135 workers before the project's lead, Colonel John Henry Patterson shot and killed both animals. He later wrote a best-selling book chronicling the event called "The Man-Eaters of Tsavo," which subsequently became a film.

To very few critics' surprise, the piece takes quite a few liberties in telling the real story of what happened with these lion attacks in East Africa, most notably introducing a completely fictional character. Despite putting the story on the table before the general public, Hollywood had its way with this story from start to finish.

The Film

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jNYuDvYVSTk

The Ghost and the Darkness was written by William Goldman, famous for writing "All the President's Men," "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," and "The Princess Bride." The screenplay was only loosely based on Patterson's written accounts of the attacks, even adding a major character in the "great white hunter," Charles Remington.

It was directed by Stephen Hopkins, who was a second unit director on the 1986 hit "Highlander" before going on to direct "A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child," and "Predator 2" before working on this African adventure. A variety of actors were considered during casting for the roles of Patterson and Remington; Paramount Pictures wanted Tom Cruise for Patterson—who seems like a poor fit to me in retrospect—and he turned the role down. Kevin Costner, Nicholas Cage, and John Travolta also showed interest in the role, but none panned out. Eventually, Val Kilmer's intrigue in the film and passion for the historic character gained him the part.

The Remington drew interest from some big names, including Anthony Hopkins, Robert De Niro, and Sean Connery. Around the same time, Michael Douglas came on as a producer of the film and ultimately decided he would take on the big-game hunter role. Both the Goldman and Hopkins have since come forward saying they weren't happy with this decision. The film then cast John Kani for the role of Samuel, Tom Wilkinson as Sir Robert Beaumont, Emily Mortimer as Patterson's wife, Brian McCardie as Angus Starling, Bernard Hill Dr. David Hawthorne as Om Puri as Abdullah and Henry Cele as Mahina. Production then headed for South Africa.

Filming took nearly four months and according to Hopkins, "was a true nightmare." He claimed production was a constant struggle with the harsh conditions of the African bush in the Songimvelo Game Reserve. Crew members were bitten by snakes and other creatures, storms slowed the filming, and it didn't help that Val Kilmer came onto the production on short notice and had a little time to prepare for the role.

Still, the crew worked nearly seven days a week for four months straight to get the film finished, going as far as using tame lions from a zoo for most of the shots, and employing hundreds of extras to portray the construction workers and Masai warriors that made up the climactic lion hunt in the latter part of the film.

After editing and scoring by famous composer Jerry Goldsmith, the film was hit theaters Oct. 11, 1996 where it turned a profitable $75 million on a $55 million budget. Critically, the film didn't fare as well. Kilmer was nominated for a Razzie award, and reviews remain mixed to this day. In fact, famous film critic Roger Ebert roasted the film's editing, writing and characters, closing out his review by stating, "I hope someone made a documentary about the making of "The Ghost and the Darkness." Now that would be a movie worth seeing."

Despite what the critics thought, the film has a wide cult following and seems better received today. Especially with hunters who praise it at as being one of the most realistic depictions of hunting ever put on the silver screen.

A completely fabricated character wasn't the only stretch for dramatic effect. The lions didn't have manes and the den of these man-eaters wasn't filled with human bones. It also wasn't found by Patterson until long after both animals had been shot.

Patterson was a Lieutenant-Colonel with the British Army when the Uganda Railway committee brought him on to oversee the bridge project in 1898. The bridge was meant to link up then Uganda with a major harbor and the Tsavo River was a major obstacle. Patterson had only been on his new job for a few days when the lions began attacking and killing the Indian workers, often snatching them right out of their tents at night. In his book, Patterson described how the attacks started small, but the animals became bolder as time went on.

"At first they were not always successful in their efforts to carry off a victim, but as time went on they stopped at nothing and indeed braved any danger in order to obtain their favorite food," Patterson wrote in his book. "Their methods then became so uncanny, and their man-stalking so well-timed and so certain of success, that the workmen firmly believed they were not real animals at all, but devils in lion's shape."

As the lions continued to pick people off one by one, the workers became understandably terrified and many of them began to flee after attempts at building fences and even large fires failed to keep the animals from attacking. Meanwhile, the British became upset that the project was being slowed and Patterson decided he must take matters into his own hands.

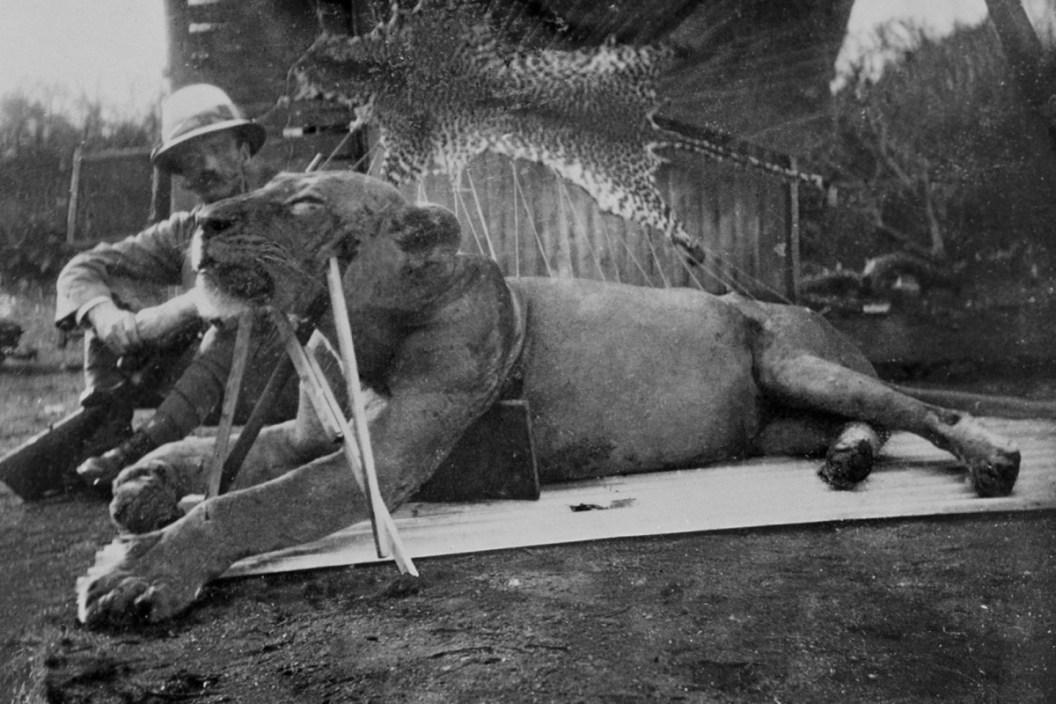

The First Lion Killed

Wikimedia Commons: Field Museum

On Dec. 9, 1898, the lions attempted to snatch a worker near the riverbank, but failed, ultimately killing a donkey instead and feasted on it. Patterson responded to the scene with a borrowed rifle he was unfamiliar with, which failed, leading to him only wounding the animal. However, the lions had only partially consumed the donkey. Figuring the lions might want to return for their kill, Patterson constructed a machan platform and had what was left of the donkey lashed to a nearby tree. The lions returned that evening, but instead of coming into the bait, they circled Patterson's position for nearly two hours, growling in the darkness.

In the movie, Kilmer's character is knocked from the platform by a wayward owl before he kills the lion. While Patterson did say an owl flew into his head during this hunt, it did not knock him to the ground.

Eventually, he spotted the shape of one of the lions in the darkness and took a shot that hit. He then decided to unload in the general direction he heard the animal. It ended up being unnecessary as the first shot had pierced the heart, killing the 9-foot-long animal, resulting in a celebration that would only be temporary.

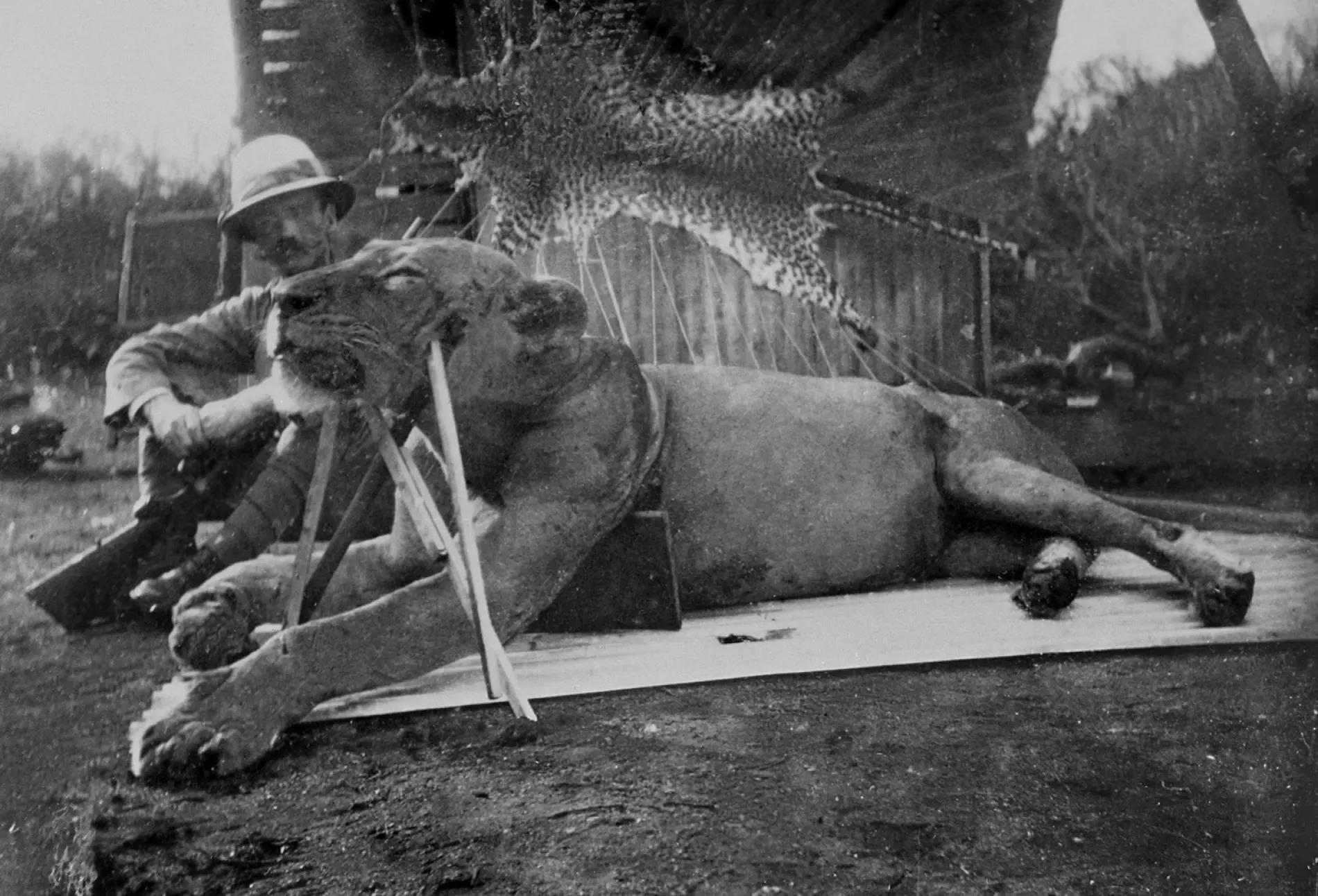

The Second Lion

Wikimedia Commons: Author Unknown

Even though Patterson had killed one man-eater, the second lion was undeterred in his quest for human victims and soon made a failed attempt to kill one of the project's inspectors in his hut. Patterson set up somewhat of a sting operation similar to what had worked before using a dead goat as bait, but once again, only managed to wound the animal. The lion made no further attempts to attack for 10 days, giving Patterson and the workers a sense of false hope that it had run off and died somewhere in the bush.

However, the lion made a recovery and attempted an attack inside the camp again Dec. 27, 1898. Patterson set up another platform in a tree and strategized a stakeout with another man serving as backup. After a long wait, they soon realized the lion was stalking them. Patterson let the lion close the gap to only 20 yards before hitting him with a .303 round to the chest.

"I heard the bullet strike him, but unfortunately it had no knock-down effect, for with a fierce growl he turned and made off with great long bounds," Patterson wrote in the book. "Before he disappeared from sight, however, I managed to have three more shots at him from the magazine rifle, and another growl told me that the last of these had also taken effect."

Patterson set out with trackers the next morning and trailed the lion when it suddenly charged out of the bush. Patterson fired a few more times and knocked the animal down, but it was still undeterred. In his book, Patterson says he was only able to escape to the safety of a tree because one of the shots had broken the lion's foot. He was then able to get one last shot off that finally ended the animal's reign of terror. In all, they found the lion had been hit six times including the shot Patterson took 10 days prior before the animal finally died from his wounds.

The Aftermath

With the lions gone, work went back to usual and the crews eventually completed the bridge in February of 1899. Patterson ended up keeping the skins and skulls of the two lions, using them as rugs for years before selling them to Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Patterson made out well on this deal, receiving $5,000 for the animals, which was a lot of money for 1924. After Tsavo, Patterson went on to be involved in the Second Boer War and World War I. He lived out his later years in San Diego, California with his wife, where he died in 1947 at the age of 79.

The Field Museum completely restored the hides of the Tsavo maneaters and put them on permanent display with their skulls. Scientists were also able to do some scientific analysis on the skulls in recent years and some scientists are now convinced the number of victims may have been exaggerated by Patterson, which some speculate was an effort to sell more books.

After analyzing the teeth and chemical levels within, they now believe the real body count for these two animals may have been closer to 35. They have also determined that the animals were likely not feeding on humans exclusively.

One common theory that attempts to explain why lions resorted to humans is the animals' damaged teeth. Not only does it seem supported by other man-eater cases, but also at least one study has shown that one lion had an infected tooth that likely made capturing its usual prey more difficult.

Other theories include a developed taste for humans scavenging human remains or that natural prey species in the area were devastated due to disease in the years prior. Whatever the case may be, the story of the Tsavo man-eaters remains one of the most famous cases of man-eating big cats in human history and will likely be hotly debated for many years to come.

For more outdoor content from Travis Smola, be sure to follow him on Twitter and check out his Geocaching and Outdoors with Travis YouTube channels.